How did the pandemic impact American mental health in April?

Editor’s Note (5/19/2020): This article includes findings from our second wave of data collection that fielded April 14 through April 22. This second wave collected another 1,000 completes using a census-balanced, national non-probability sample. The new information, shared below, examines the mental health impacts of the coronavirus and what has changed since our first wave of data collection at the end of March. Learn more about the ICF COVID-19 Monitor Survey of U.S. Adults.

As we revealed in our initial mental health findings (Wave 1), many Americans reported experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression at the end of March. This was not surprising, given the increases in both unemployment and fatalities caused by COVID-19—and the sense many had that the worst was yet to come. But what about April? Did American mental health improve, or worsen?

This report takes a second look at the mental health of Americans—about three weeks later—as the pandemic progressed in the United States and around the world. Specifically, we re-examined the relationship between mental health and economic outcomes and considered substance use within the context of mental health.

In mid-April, Americans continued to experience symptoms of depression and anxiety.

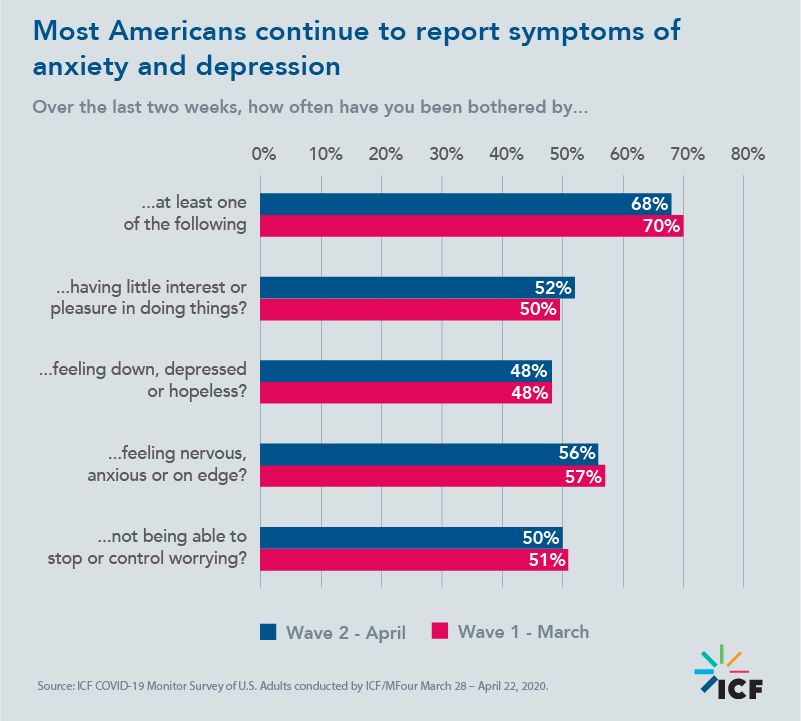

In Wave 1, 70% of Americans reported experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety on at least several days over the past two weeks. In Wave 2, this percentage decreased slightly to 68%. Specific symptom percentage comparisons between Wave 1 and Wave 2 are presented below.

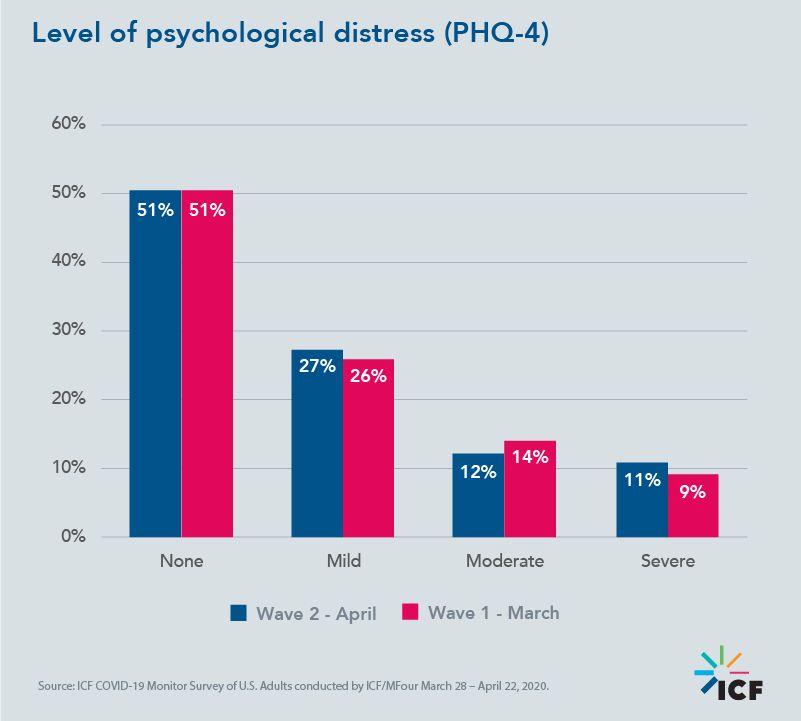

Using the Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety (PHQ-4) scale, nearly a quarter (23%) of Americans in both Waves 1 and 2 reported having moderate or severe psychological distress.

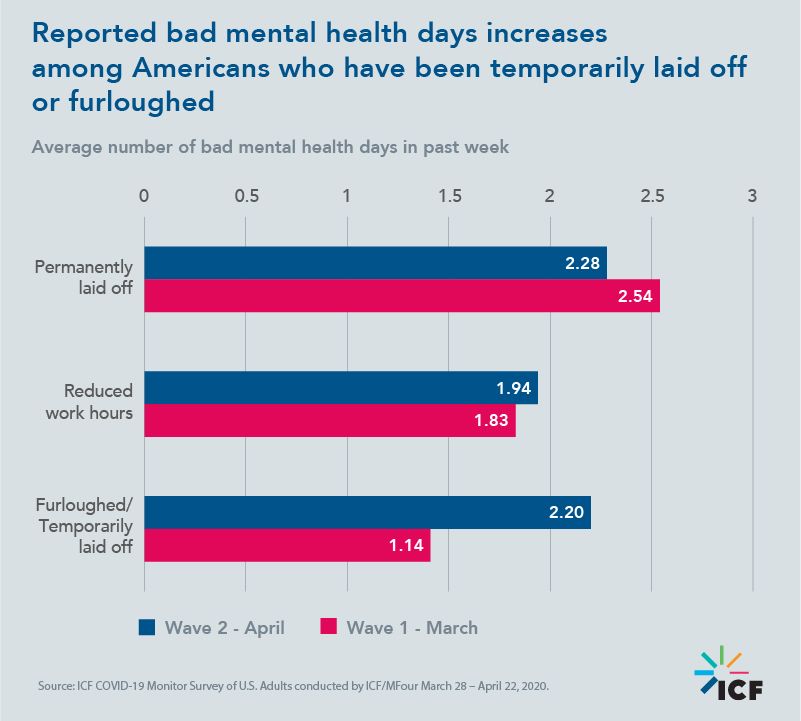

Reported bad mental health days increased in mid-April among those who have been furloughed or temporarily laid off due to COVID-19.

At the end of March, Americans who had been permanently laid off or had their work hours reduced reported a higher average of bad mental health days than those who had been furloughed or temporarily laid off. However, in April, Americans who had been furloughed or temporarily laid off reported a relatively similar average number of bad mental health days as those who were permanently laid off. All differences are statistically significant.

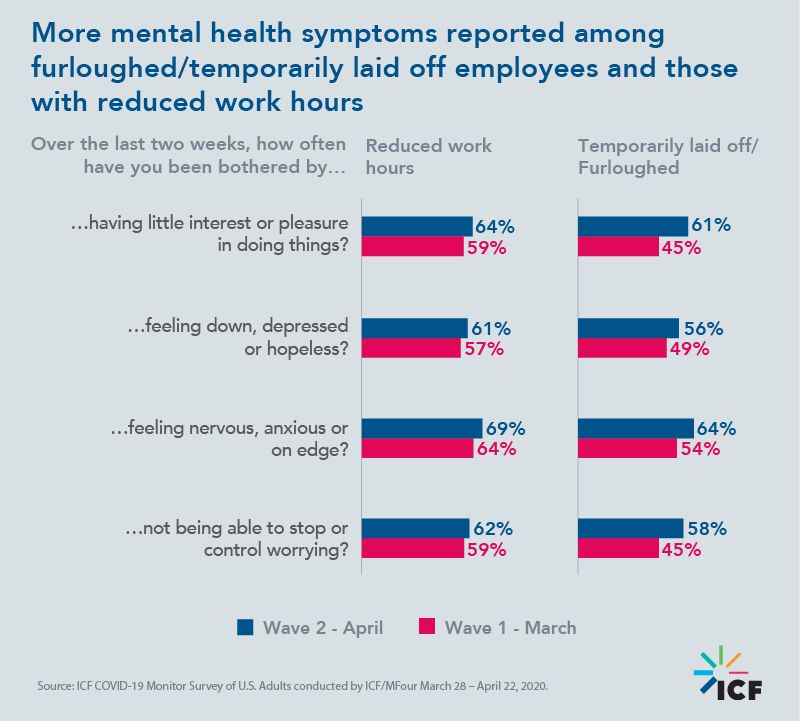

In April, Americans who have been temporarily laid off or had work hours reduced due to COVID-19 reported more mental health symptoms than in March.

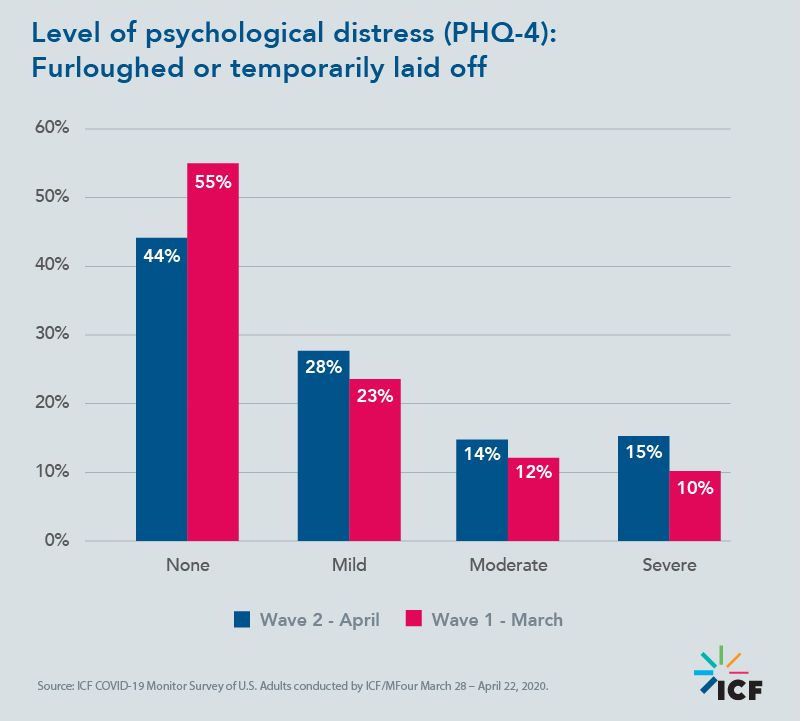

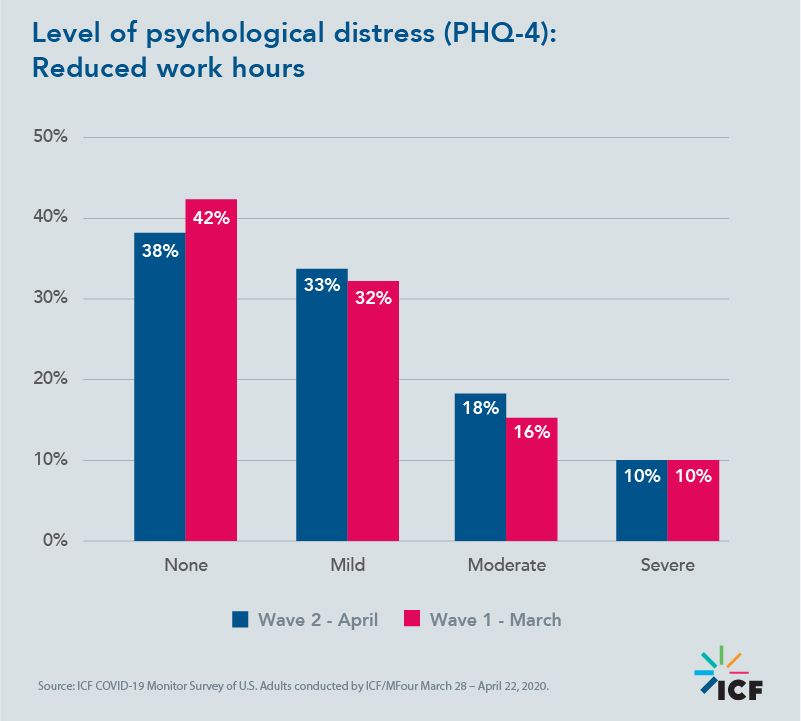

As we entered our second month of lockdown, COVID-19 and its economic impacts continued to take a toll on American mental health. As shown in the chart below, furloughed/temporarily laid off employees and those with reduced work hours reported more mental health symptoms in April than in March. All differences are statistically significant.

In April, moderate and severe psychological distress increased among those who were furloughed/temporarily laid off. Moderate psychological distress increased among those who had their work hours reduced.

In April, smoking and drinking increased—and these behaviors remain highly correlated with self-reported mental health.

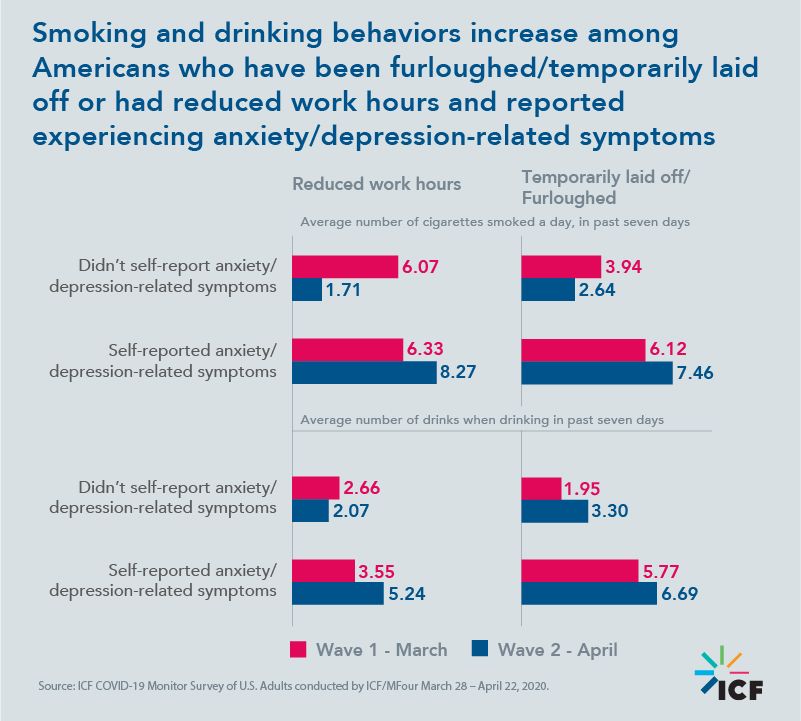

As we discussed in our Wave 1 mental health findings, financial and health strains caused by the coronavirus were related to poorer mental health. Poorer mental health was related to increased drinking and smoking behaviors. In Wave 2, we saw sustained and slight increases in these behaviors.

Examining responses from Americans whose work status had been negatively impacted (furloughs, temporarily laid off, or reduced work hours), we found an increase in smoking and drinking behaviors among those who had reported experiencing at least some days of anxiety/depression-related symptoms. All differences are statistically significant.

Policy implications

As outlined in our initial mental health findings, health, public health, and behavioral health officials must recognize and attend to the mental health and substance use needs of citizens in the short-, medium-, and longer-term. While physical health and safety remains a top priority, officials should scrutinize the current infrastructure and prepare for an uptick in behavioral healthcare needs caused by COVID-19 related depression, anxiety, substance use, and suicidal behavior. The addition of these individuals to the pre-existing population of Americans with behavioral health challenges presents a current and future need—one that is not short-lived and will likely not dissipate in the near term.

Emergency response funds being directed to state and local jurisdictions provide a first wave of reinforcement to support this increased demand. Other efforts such as (1) enhancing screening efforts for early detection; (2) focusing on therapeutic and medication continuity for existing consumers; (3) mitigating access barriers such as financial and social distancing requirements; and (4) directly combatting the ever-present stigma associated with seeking help are essential to promoting the mental health and wellness of American citizens.

Watch this space

How will public perception change as the pandemic continues? How will mental health be impacted by the reopening of non-essential businesses in some states? We will continue to report key findings from our data collection efforts over the coming weeks and share this information with public health officials in support of their response to COVID-19. Sign up to receive alerts as we roll out upcoming results and package our insights into reports.